Spreadsheets are a go-to mechanism for coping with indecision. I feel safety in the grey walls of those tiny cells. I can sow variables in the endless fields of cells, rich with possibilities for manipulation. Whether I’m exploring infinite budget options, assigning criteria to ranking wedding venues, or collecting data to refute my partner’s claim that I “never get home before 6,” I’m living life in a spreadsheet. I often dream spreadsheets.

In this post, I’m excited to introduce a spreadsheet that’s really important to me, and will be the focus of a good deal of this blog moving forward. Please give a warm welcome to the…

WHAT AM I DOING WITH MY LIFE SPREADSHEET!

All credit for this model goes to the brilliant Simon Rilling.

What’s Math Got to Do With It?

Oh, you beautiful, misguided golden finch.

I read about decision making and risk evaluation in Robert Harris’s Introduction to Decision Making, I was surprised by my own delight. The idea of letting math take the wheel appealed to my faith in science, and the idea that you could write a formulas to predict joy was at once comforting and horrifying. I’ve only begun to scratch the surface of this topic and hope to devote several more posts to risk management.

The Simon Rilling method is loosely inspired by this risk evaluation formula:

EV = sumn (pn x rn)

The expected value (satisfaction in a career choice) is found by adding the values of each possible outcome, diminished by its own probability.

Robert Harris’s Example: Should I go scuba diving this weekend? If I do, there is a ninety percent probability that I will have a lot of fun. I quantify this great fun as 10 fun points. There is also a ten percent probability that I will get hurt, which I quantify as minus 20 fun points. If I make the other decision, to stay home, there is a ninety-nine percent probability that I will be bored, represented by a minus 2 fun points, and a one percent probability that something exciting will happen, which I represent as five fun points (half as exciting as going scuba diving). Our expected value worksheet looks like this:

Probability Reward

_____ .9 x +10 = +9

|

|_____ .1 x -20 = -2

Y|

_Scuba?_| Total = 7

N|

|_____ .99 x -2 = -1.98

|

|_____ .01 x +5 = + .05

Total = -1.93

Here we see that the expected value of going diving is 7, which is much higher than the expected value of staying home, which is a negative 1.93.

My Process

First, I set the criteria for happiness, based on my limited self-knowledge. Is it a good fit, does it fuel me, will it pay me, and can I sustain it as a career? I broke these down further into measurable qualities.

Then, I set a timer and wrote down as many desirable paths as I could think of. Some are variations on a theme (therapy with college students v.s. adults) and some are total wildcards (touring punk cover band.)

Next, I took a stab at guessing the probability of success for each career against each criteria.

The Results

This whole thing reminded me of the studies where researchers run your own voice through a modulator, and find that we generally can’t identify our own voices even when they’re only lightly disguised.

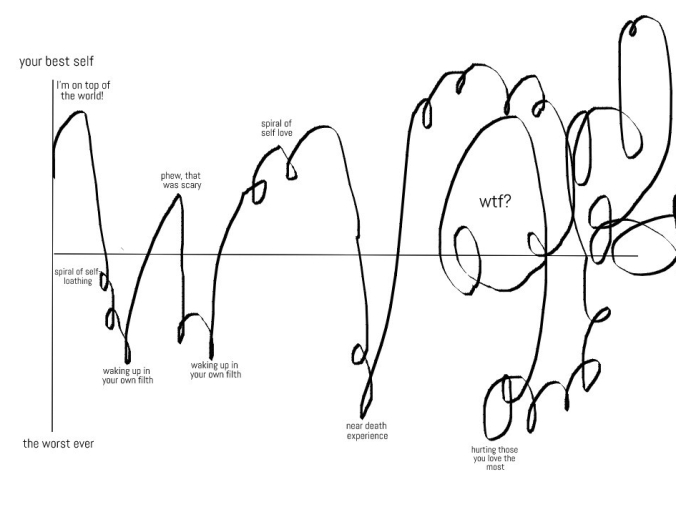

I went through my process with the last column hidden so I couldn’t see what my assigned values were adding up to. The result was a statistical analysis that largely mirrored my emotional one for the last 10 years.

When I was 20, I took a career test. It told me I should be a researcher or a dentist. I should have learned that I like people and also structure. Instead, I laughed about the idea of being a dentist and threw the paper away.

The top choices, according to my math are:

- Organizational psychology focused on workplace culture

- Writing about trying out different jobs (pure wish fulfillment)

- Counseling (relationship or individual)

- Writing about research (ala Mary Roach)

The Meaning of the Dream is In the Interpretation

Dreams are the likely the result of our mind trying to process the mess in our brains. The value of symbols in dreams is primarily in our interpretation. If you think the dream of a monkey was about your boss, that’s a more valuable piece of data than to learn that most people dream about monkeys during warm weather.

The way I interacted with the process – where I assigned higher or lower values, and the reaction I had when I heard organizational psychology had won – those are more helpful data for me in this process than the results themselves.

Pivot Procrastinator’s totally reasonable measures of success:

1. Money.

I’ve been in nonprofits my whole life and so I am only now realizing that money is important for supporting human life and that I would to earn some. Not a ton, but above the average household income in my city would be nice.

2. Having a career fuels me and fits me. I broke this down into:

- Pace. As a metaphor, I’m really into “Fartlek,” the Swedish art of pacing in long-distance running. I’ve learned that I thrive when I have the opportunity sprint short distances – to work intensely on short projects – and then to recover with a calm pace.

- People. As an extravert, I am fueled by people.

- Creativity. Writing is my creative outlet of choice, but I’m flexible.

- Structure. Success in this area means having some external structures and deadlines.

- Learning. As previously discussed, I am a huge nerd.

3. Balance, which is broken down into:

- The opportunity for flexibility: to travel and eventually to parent. My dream is that my partner and I are able to each work 30 hours a week while our kids are young. Perhaps a crazy dream.

- Working, on average, a reasonable number of hours per week. Reasonable is relative. Fewer than 50 would be great.

- Emotional balance. I want to be emotionally invested and know that what I’m doing matters, but not to feel the weight of humanity entirely on my shoulders.